Mutiny at your workshop

Everyone who’s convened has been there.

Sometimes it looks like a huddle of people talking at lunchtime, avoiding your eye contact. It can be a friendly chat at dinner, “you should really do x”. Or a more direct hand up in plenary, "we've been talking and we just don't think we're focusing on the right thing."

Psychologists talk about ‘emotional contagion’. This is where one person's emotions and behaviors directly trigger similar emotions and behaviors in other people. Emotional contagion means that if you don't nip it in the bud, you can have a full blown mutiny on your hands.

In my experience, there are some important moves you can make to prevent it happening in the first place. Here they are:

Everyone who’s convened has been there.

Sometimes it looks like a huddle of people talking at lunchtime, avoiding your eye contact. It can be a friendly chat at dinner, “you should really do x”. Or a more direct hand up in plenary, "we've been talking and we just don't think we're focusing on the right thing."

Psychologists talk about ‘emotional contagion’. This is where one person's emotions and behaviors directly trigger similar emotions and behaviors in other people. Emotional contagion means that if you don't nip it in the bud, you can have a full blown mutiny on your hands.

In my experience, there are some important moves you can make to prevent it happening in the first place. Here they are:

What prevents you from hosting a successful gathering? What are the solutions?

All talk and no conversation

People get bored, frustrated, tired. Unable to remember of process all the information they have levelled at them.

Solution: Skip the presenters, allow people to talk. If it’s a technical topic people know don’t know enough about, have a punchy presenter and immediately allow time to discuss after each one.

The same people always dominate

The usual suspects, make their points first. Often these can also be the most passionate about the topic and or the most discontented, skewing the groups’ perception of the meeting.

Most of us have probably played both of these roles before. We know that both are frustrating. As the dominant person you are left feeling like you are not learning from your peers. As the quieter one, you leave having missed the chance to share your best ideas and often feeling like the dominant voice was not the most impressive.

Solution: Always use participatory processes. If nothing else, break people up into tables of 4, ask them a simple, powerful question about the topic in hand and make sure they record their answers on paper, so they know their ideas are being listened to.

If you want to do a better job, create the conditions for people to share their ideas through different mediums. Allow people to draw, build, talk, act and write. Not everyone explains best with words.

You don’t really care about this issue your asking people to talk about

People can see straight through it if you ask them a question about something you don’t really know or care about. Or if you ask for their ideas on an issue that you already have the answer to.

Solution: Many of us host rolling events that we ‘have’ to do regardless of whether we have something to solve. It’s always worth going back to ask ‘what was the purpose of bringing this group together in the first place?’ Was it to gather intelligence from an esteemed group of people? Was it to allow them to network and connect? These insights can often get up back on track, have them top of mind when you’re picking a design. Do you genuinely want to hear their ideas on an issue? What is the question you’d really love to ask them? If you are genuinely excited and interested in a topic, then don’t be afraid to express that. Be bold and tell a story about why this is important to you and ask your burning questions, not your average ones.

You are skating around the massive elephant in the room

If there’s dissent, it will only be amplified when you bring people together even if they don’t get a chance to speak to each other.

Solution: If someone takes a leap and brings up an issue that derails your plans, but you know if important, acknowledging it. If you have time split the group up and ask people to discuss and capture their key challenges on the topic. Even better, ask them to come up with solutions.

Your presence as a facilitator is shaky

Are you trying to do too much, overseeing the content, speakers, meeting logistics, design of the event and giving participants instructions too? Are you nervous, distracted or overwhelmed? This happens to us all, but you can make it less stressful by admitting to yourself that this is likely to happen if you don’t plan adequately.

If this is the first time you’ve convened a group, it’s natural to feel unsure how the dynamics will play out.

Are you asking yourself “who am I to convene this group?” This is such a common feeling for people who have taken action to convene for the first time.

Solution: Ask for help. Get better at delegation and if nothing else make sure you at least one person to help who can take control of logistics so you don’t have to think about whether you have lunch coming on time or enough post it notes.

Name your nerves when people arrive. Frame up the session by saying ‘We have never convened this group before. We don’t know what you’re thinking, what you care about, what opportunities or challenges you might face. This is an experiment for everyone. We will adapt the design to meet the needs of the group.’

If you look around and no one has taken the leadership to convene this group of people, then give yourself a big pat on the back for doing it and let that bolster your confidence.

Finally, simplify and breathe. Make your design and instructions as simple as they can be. Try and take 1 deep breaths before you start and stand feet forward and head floating up like a balloon (HT our brilliant former Ballerina Alina Faye who taught us this at our Remarkable Events workshop in July).

Your hosting team is shaky

This can happen for many reasons. If the core team don’t know each other very well, if there’s internal politics, if there’s a lack of preparation and roles have not been well divided up, it shows.

Solution: Spend at least 6 weeks planning a major event. Have weekly calls, expect your event design to pivot as new information comes to light, give yourself time to sleep on it and iterate it as you go.

You have the roles and responsibilities all mixed up

The right hand isn’t sure what the left hands doing. The hosting team is picked for their role in the organization, rather than for their skillset.

Solution: Make sure people are invited to contribute in ways they feel valued and comfortable. Someone might enjoy design more than facilitation. Others might be a confident at hosting the opening remarks. Another team member might be better at giving clear instructions or have the charisma to host the ‘fun’ sessions. Where possible play to people’s strengths no matter where they sit in the power structure of the team.

You are trying out a new event design that you’re unsure of

You feel nervous about whether it will work and you will never know until you are in the room on the big day.

Solution: Be proud of yourself that you’re learning. Spend a good 6 weeks, meeting for an hour each time, to go over and over this, refining it and making sure everyone is totally clear on how to run the session in advance. Have power point slides with clear instructions on the tables for participants and practice running through with colleagues until you feel good about it.

Yes, but

This is always one big fat experiment. Conditions are not always ideal. I have been designing and facilitating events for 10 years and I still make mistakes like these on a reasonably regular basis. The key is to have awareness about them in advance, to try to plan as much as possible and to make sure you spend time after each event thinking through:

What went well?

What would I do differently next time?

This is how we get better.

Launching a new program for system entrepreneurs who are ‘halfway through’

We are excited to announce the launch of our new peer-to-peer learning program, The Systems Sanctuary, for systems entrepreneurs who are head down, sleeves rolled up and have been working on their systems change project for at least two years.

We’ve chosen this group because we see a gaping hole in support for people who are really in the thick of it.

We are excited to announce the launch of our new peer-to-peer learning program, The Systems Sanctuary, for systems entrepreneurs who are head down, sleeves rolled up and have been working on their systems change project for at least two years.

We’ve chosen this group because we see a gaping hole in support for people who are really in the thick of it.

Consultants can help you get started, but it’s from two year mark on wards that it begins to get really tough. Stakeholders are watching you, you have to make tough decisions about money, strategy and collaboration, and often try to tell a compelling story at the same time.

Systems change projects are slow burners and can look messy and unfinished to the outside world, but that doesn’t mean they’re not building the foundations of something that could change everything. We’re placing our bets on the people who are ‘half-way through’. (*and hoping they will remain committed if we tell them it will all be over in 4 years!).

Peer-to-peer learning

Front and center of our program is a belief in the experience of the people we are bringing together. We’re focusing on peer-to-peer learning because we found spending an hour with someone who actually understands what you’re talking about is absolutely invaluable. Peers have ideas you can borrow, models and frameworks that are relevant to your challenges and most importantly can bring a sense of camaraderie and humor to your world when you really need it. Systems change can be heavy and serious, but it can also be joyful and inspiring.

Who’s behind it?

We have partnered with seasoned systems entrepreneur Tatiana Fraser of MetaLab, to create the program we wished we’d had when we were leading our systemic change projects in the UK and Canada.

We bring our collective experience of leading a systems change work in the UK and Canada to The Systems Sanctuary. Prior to launching The Systems Studio I co-founded and co-led The Finance Innovation Lab for 8 years, an award winning project designed to empower positive disruptors in the financial system. Tatiana has 20 years of experience creating strategic learning communities, building movements and working across difference including Indigenous, racialized and economically marginalized communities. Co-founder of Girls Action Foundation and co-author of Girl Positive (Random House 2016), she has worked to re-frame the narrative around gender equality and to advance the leadership and empowerment of girls and young women.

But this program isn’t about us. We will be using our diverse network to bring together a really interesting mix of people from across the globe, setting up the conditions for great conversation and then getting out of the way, so they can talk about what’s really meaningful to them.

Who should join?

We are seeking a diverse group who are working on different systems and challenges from public services, to poverty, to climate change, members of professions and beyond.

We especially welcome applications from those who have been disadvantaged by our current systems and are open to applications from all over the world. We will work out time zones as to fit our cohorts.

We know this group don’t always have huge resources and are pushed for time, so the program will be short, punchy and affordable and will run from February to July 2018. You can find full details and register online here.

The future

Our ambition is that the Sanctuary becomes a platform from which we can launch multiple communities of practice for different groups within the field of systems change.

If you know a group of systems changers who need a peer-led community of practice, get in touch.

Rachel@thesystemstudio.com

The Systems Entrepreneur: What’s in a name?

‘Systems leader’, ‘systemsprenuer’, or ‘systems entrepreneur’. Pick your favorite. Regardless of which one you go for, the concept is emerging with SSIR, HBR and MIT all using it, along with a cluster of philanthropic foundations and consultancies.

This blog originally appeared on the Kumu Medium channel.

‘Systems leader’, ‘systemsprenuer’, or ‘systems entrepreneur’. Pick your favorite. Regardless of which one you go for, the concept is emerging with SSIR, HBR and MIT all using it, along with a cluster of philanthropic foundations and consultancies.

But what defines a systems entrepreneur?

Their intention is systemic change

Systems theory tells us that we don’t actually ‘change systems’, instead we cultivate the conditions that encourage a system to change itself.Nevertheless, the defining characteristic of a systems entrepreneur is their understanding that things don’t change if we work only on the symptoms of major problems. We have to understand the underlying forces that keep things as they are.

So, rather than take ‘ugly’ fruit that might otherwise be thrown away and turn it into healthy snacks, a systems entrepreneur would ask ‘why is fruit being wasted in the first place?’

They might convene the food industry giants, the policy changers, the social entrepreneurs and ask them to share their experience of the problem. Map the current dynamics together to help the system see itself better. They might use this intelligence to come up with a plan. Find resources to build connections across the system, create documentaries that highlight the current problems of the food system, build accelerators for the most promising alternatives, they could lobby for policy change that will make it easier for these alternatives to emerge. Systems entrepreneurs hold their plans lightly. They take their steer from the community itself, rather than from desk research. They iterate, learn, and change direction as the movement advances and they understand that all of this work takes time.

“Knowing that there are no easy answers to truly complex problems, system leaders cultivate the conditions wherein collective wisdom emerges over time through a ripening process that gradually brings about new ways of thinking, acting, and being.” — Peter Senge.

Their key skill is facilitation

Systems entrepreneurs are often natural ecosystem builders. It’s almost a personality type. They connect unlikely allies, build networks, they help people find others who want to change the same thing. Kevin Jones called these people “Community Quarterbacks”, Geneva Global describes them as “a person or organization that facilitates a change to an entire ecosystem, by addressing and incorporating all the components and actors required to move the needle on a particular social issue.”

Either way, they build momentum by creating and capturing the energy of key people within a system and get them organized in new constellations to intervene.

They are also often natural diplomats. They can wear many hats, talk to senior and junior, activist and executive. They find language that brings people along together, rather than alienates.

As a result, getting good at facilitation is the key skill of a systems entrepreneur. Facilitation is important because it marks the shift in a mindset from us thinking we can ‘make change happen’ towards one where we create the supportive conditions where the people lead change themselves. As Lucho Osorio-Cortes a markets systems specialist at the BEAM Exchange says “Facilitation, is the creation of appropriate conditions for the market actors to change their system, in ways that make sense to them, at their own rhythms and maximizing their own resources.”

They get off their bum and make stuff happen

They initiate. They create projects and programs and coalitions and incubators that didn’t exist before. They are entrepreneurial in nature, even if money isn’t the value they create.

They also take personal risk, sometimes financial risk too. As disruptors of the status quo, their role is often questioned (‘who are you to convene?’). They have to lead strategy that goes against the wishes of powerful actors, without complete knowledge of where they will end up.

So what?

Systemic problems require systemic approaches, but instead we still rely on traditional approaches to social and environmental change, funding ideas that work on symptoms not causes.

There is a growing movement of systems entrepreneurs who have been experimenting with systems change theory and are learning what works and what doesn’t in practice, but their work is often invisible and undervalued. One step away from the impact, it can be hard to fund and as a result the field doesn’t have the coherence nor the visibility to have the impact society needs.

To help them succeed, two things badly need to happen:

- We need to bring together the systems entrepreneurs. To connect, learn and find peer support.

- We need to get better at funding them. This is starting to happen. Indy Johar is working on sparking a movement around ‘systems venturing’. Bobby Fishkin and colleagues in San Francisco are convening a growing group around impact investing for systems change and several groups of philanthropic funders have met to start to work this out including a retreat hosted by SiX last year in Canada.

We plan to get organized around solving these problems in 2018. If you are interested in helping to make this happen, please do get in touch rachel@thesystemstudio.com.

Interview: Systems change network builders

Some things I’ve learnt:

- The people who live and breathe in the system are those who have to come up with the solutions to change it. Inputs from external experts are useful but they have to make sense to the people in the system.

- The system, not the poor, must be the unit of intervention if we want sustainable impact at scale.

- You have to listen to the system. Truly listen; without confirmation biases, without ego, without expectations, without intention, listen quietly and openly.

Benjamin Taylor

Benjamin has 20 years experience at public service transformation in the UK. As Chief Executive of the Public Service Transformation Academy, a not-for-profit social enterprise awarded the Cabinet Office Commissioning Academy, he is a leading thinker on system leadership, service design and transformation. He is an accredited power+systems trainer, a visiting lecturer in applied systems thinking at Cass Business School, City University, and has lectured at Nottingham Business School and Oxford Said/HEC Paris.

Some things I’ve learnt:

- Learn the difference between complexity and complicated, technical challenges.

- Dealing with complexity requires collaboration. To succeed co-design, enlist discretionary effort, be honest, accept you don’t have all the answers.

- Community is the antidote to uncertainty.

- To get more power, you have to give up control.

- Take time to ‘see’ the system. Think about illuminating the rules of the game, the effort and learning it takes to stay dysfunctional, the power of community.

- Listen out loud, ask good questions, start from strengths.

- Ask: Who do we want to be? What could I do to create a shared view across the whole system for the people in it? What thoughts or questions does this raise for me?

- Confront people with their gifts.

- Think massive, start very small. Help people to explore and experience change and shape it, within limits.

- Make your best prediction about how your changes will land. Take responsibility for all the outcomes, the actual experience of all the people in your organisation and all the people in your community, however great or sh*t it is. And as it turns out different from your prediction (because it will), think about why that is. Then you’ll be working in learning world too.

- Experimentation is the antidote to certainty, confront people with reality.

- Real change is dirty work. Don’t fool yourself you’ve learned anything until you have tested it in the real world. And even in the ‘real world’, don’t think you are learning if you’re not predicting and reflecting. When we take responsibility for learning about outcomes, we will get there

Some of the challenges:

I see the locus of challenges within our communities of systems practice, rather than externally:

- There are a growing number of systems ‘gurus’ who in my view are all about creating ownership to develop power. This is well covered by the title of a blog piece Richard Veryard wrote on a related subject: ‘Wrecking synergy to stake out territory’. (could you share the link, I cant seem to find this)

- There are ‘Systems Curmudgeons’, the people who stand on their expertise and attack those who ‘get it wrong’.

- And early-stage systems enthusiasts who create new movements that follow a ‘hype cycle’ which ends in failure, that is completely predictable to those who know the history.

- Funding can be a problem too – funding initiatives that take systems thinking out of managing business risk. Doing so makes programmes less organic, less well-adapted, and less effective.

- I think that the only way to counteract all of this is to patiently and consistently build network links, explain weaknesses and try to come up with an overarching narrative that talks about what each model explains, explains what they don’t explain, and explains why.

Systems of interest

I work on helping public services in the UK (and Australia) to transform themselves. More broadly, helping to change people's experiences of organisations, as employees and as customers/citizens. And, wider still, helping people to see systems and change them.

My systems change network

I am a systems change network enthusiast – more of a curator and a learner/sharer than a joiner. I work at the overlap of theory and practical organisational change. Some of the networks I’ve been involved in:

- SCiO – Systems and Cybernetics in Organisations – the best learning group I've experienced. It includes Practitioner development days and Peer speaker days with about 250 people. This is cheap and accessible.

- The London design and systems thinking meetup group (200+ folk)

- On LinkedIn, Systems Thinking Network and on Facebook, The Ecology of Systems Thinking.

- The ISSS and UKSS (International and UK Systems Societies). I am a visiting lecturer on the very interesting Cass Business School undergraduate Applied Systems Thinking course.

- The Public Service Transformation Academy, a not-for-profit social enterprise I founded, which supports capacity and capability building for public service leaders, and the Cabinet Office Commissioning Academy, which we run. The PSTA will publish its first annual 'State of Transformation' report on public service transformation in April next year - collaborators and sponsors are very welcome!

- Model Report is list I curate as a way of organising articles and links on systems thinking.

- RedQuadrant is a network consultancy which very much welcomes applied systems thinking. We work with about a hundred associate consultants a year from a pool of over a thousand.

My inspiration

- Barry Oshry's work –Power and Systems and The Systems Letter. Watch Barry at SCiO and PwC.

- Navigating Complexity, Arthur Battram

- Viable System Model, Stafford Beer – start with the explainers on SCiO then go on Beer, and try Patrick Hoverstadt's Fractal Organisations. Patrick’s Patterns of Strategy, co-authored with Lucy Loh, should transform the field of strategy and is enormously valuable in many contexts.

- For a 'the process as a system', try Joiner's Fourth Generation Management, Scholtes' Leader's Handbook and Team Handbook, for public services try Richard Selwyn's free Outcomes and Efficiency, dip a careful toe into I Want You to Cheat and other works by John Seddon and from the same stable, but stepping into ‘the community as a resource’ or strengths-based approaches, try Richard Davis' Responsibility and Public Services.

- For a beautiful little summary that goes way beyond its title, look for Total Quality Management by Develin.

- The Little Book of Beyond Budgeting by Steve Morlidge is another tiny read that sneaks systems thinking in by the back door and makes total sense, and Beat the Cuts by Rob Worth brings us back around to a Deming-esque view of public service processes (not necessarily systems – but critical to know).

- Try anything from Peter Block, especially Flawless Consulting and his work on Abundant Community. Anything from Marv Weisbord, particularly the short Tools to Match Our Values, and some Ed Schein... and I could go on! Adaptive Leadership by Heifetz and Lipsky is valuable too, as is the literature on 'wicked problems' and related concepts.

- I think there's little more powerful in organisational life than combining the Viable Systems Model with Elliot Jacques' Organisational thinking (updated, and with valuable additions, not all of which I agree with - in the brilliant but very academic Systems Leadership Theory by Macdonald et al). Luc Hoeboeke's Making Work Systems Better is perhaps the only work I know that combines them, as I do in my work.

- Two fairly recent additions are Ed Straw's video Stand & Deliver: How consultancy skills and systems thinking can make government work

- And I haven't even mentioned soft systems method, Nora Bateson's work… or the book I co-authored (not systems thinking in a meaningful way, but opening up thinking) - The 99 Essential Business Questions.

As a systems network builder, how do you fund yourself?

All pro bono! I can't help myself – I just find myself doing it – and I've never received a penny (well, about £150 per 'visiting lecture' – but that means forgoing a bit more income for a consulting day). We don't even pay expenses at SCiO. However, it shades right across my day job(s) at RedQuadrant and the PSTA, so I support myself somehow. One day I would like to make all my living in systems-related work, (though isn't every type of work systems-related?), and I certainly get amazing value from the networks I am in.

Interview: Systems change network builders

Some things I’ve learnt:

- The people who live and breathe in the system are those who have to come up with the solutions to change it. Inputs from external experts are useful but they have to make sense to the people in the system.

- The system, not the poor, must be the unit of intervention if we want sustainable impact at scale.

- You have to listen to the system. Truly listen; without confirmation biases, without ego, without expectations, without intention, listen quietly and openly.

Lucho Osorio-Cortes

A markets systems specialist at the BEAM Exchange and Practical Action Consulting. He has more than 15 years’ experience in international development and specialises in the facilitation of market systems development and organisational learning. Lucho coordinates The Market Facilitation Initiative (MaFI), a working group of the SEEP Network helping practitioners to become more effective facilitators of inclusive market development programs.

Some things I’ve learnt:

- The people who live and breathe in the system are those who have to come up with the solutions to change it. Inputs from external experts are useful but they have to make sense to the people in the system.

- The system, not the poor, must be the unit of intervention if we want sustainable impact at scale.

- You have to listen to the system. Truly listen; without confirmation biases, without ego, without expectations, without intention, listen quietly and openly.

- Market engagement is empowering in itself. We do not always need to empower ‘poor’ people before they are ‘ready’ to engage with other market actors.

- Never trust actors who always say yes and never question you as a facilitator.

- Never underestimate the transformational power of seemingly irrelevant actors. Let them ‘do their thing’ and pay attention to the reactions of the system.

- Every event in the system has the potential to change it, opening new, sometimes unexpected, entry points and closing entry points that we thought were open. Flow with the energy and rhythms of the system.

- Scaling up is a fractal process. The whole system has to resonate with the solutions implemented in a fragment of it. The more the fragment has the properties of the wider system, the easier the solutions from the fragment will be accepted and adopted by the broader system.

- Facilitation is not always equivalent to ‘light touch’. Facilitation is the creation of appropriate conditions for the market actors to change their system in ways that make sense to them, at their own rhythms and maximizing their own resources. Sometimes intense and long-term investments have to be made to get the system moving.

- Market systems can deliver sustainable impact at scale if three processes take place at the same time: empowerment for engagement, interaction for transformation and communication for uptake.

- We see what we measure; we measure what we value.

- Do your homework to avoid obvious mistakes but then jump in the water and learn as you swim.

Some of the challenges:

- Firstly, in my view there is a huge disconnect between theory and practice.

Theorists often say, ‘we get it’, but they don’t. What they don’t get is that the deeper you get into it, the more counter intuitive this work is. At the same time practitioners in the field will say ‘I have practical experience, I get systems’ and this is dangerous too. The two groups could learn a lot from each other.

- Secondly, people in development are often very keen on the ‘hard’ aspects of systems change; economics, viability, measurement and evaluation, program design.

Bureaucrats can digest this. But when you look at what makes or breaks a project, so often it’s the skill of facilitators. How they see the world and interact with it (e.g. the market actors and the forces that influence their behavior).

Facilitating systemic change requires skills and attitudes that bureaucrats can’t grasp and or measure easily with their current paradigms and practices. This makes it difficult for donors and other development agencies to invest because they can’t see the importance of the human element and the need to enable flexibility, uncertainty, trial-error-learning, and adaptability in the development process.

- Thirdly, the discourse of value for money dominates donors’ mindsets and is dangerously permeating the perceptions of the public.

But no functional system can be resilient without what I would call “exploratory inefficiency”. There is a risk that if we don’t produce evidence of the effectiveness of the market development approach the fad will go and donors will look elsewhere. But there is a paradox: under the traditional donor-implementer paradigm, the approach finds it very hard to deliver on its promise of sustainable impacts at scale and, therefore, to produce evidence of its success.

As a result of all this, MaFI is currently in the process of evolution from a general focus on market systems development to one on that explores the cognitive aspects of facilitation of market systems development programs. Questions like - how do successful facilitators behave? How do they think? What paradigms and tools they use? How do they identify key stakeholders and engage with them?

Systems of interest

I work on market systems and peer-learning networks in Latin America, South Asia and Eastern Africa. Most of my work is designed to help practitioners gain a better understanding of how to use a systems lens in their efforts to make markets more inclusive, productive and efficient.

If these practitioners are more effective at facilitating (enabling, catalysing) structural changes in market systems, more people will get out, and stay out of poverty for longer periods of time. This will happen with less effort, less cost and less friction, compared to traditional development approaches that focus on the poor and deliver solutions devised by experts from outside of the system.

My systems change network

The building blocks and principles that make up the field of market systems development have been around for many years, but the communities of practitioners who see themselves as part of this field started to form during the 2000s. There are many platforms where practitioners connect. I have been involved or participated in the creation of:

- The SEEP Network

- The BEAM Exchange

- The Latin American Network for Market Systems Development

- The Academy of Professional Dialogue

For example, I helped to create MaFI, which aims to close this gap in knowledge by advancing practical principles and tools that assist practitioners working in pro-poor market development to move from market assessments and program design to implementation.

During my time as the coordinator of MaFI (since 2008), the group has produced learning products based on MaFI's online discussions, webinars, and in-person meetings, and also seeks to influence the debate about rules and principles of international aid that hamper inclusive market development.

The value of the market systems development field is relatively big and growing. I would guess that, currently, there are around 20-30 market systems programs running, worth around $3-10 million each. Some people may argue that there are more market systems development programs but I have seen many of them that fail to use the principles of the approach properly. When it comes to the implementation of these programs, the devil is in the detail. For example, how you select and train your staff, how you build a culture that enables open sharing of mistakes and learning, how to change tactics and even strategy quickly, how to use less program money and more systemic resources, how to pay attention to early indicators of change that give you clues about the future behavior of the system; how to select, engage and communicate with market actors, how to help them experiment with new ideas, etc.

My inspiration

- Quantum physics (the duality of nature -e.g. light- and the need to embrace probability and uncertainty). The Tao of Physics.

- Theory of relativity (the importance of the different perspectives of the observers, the connection between matter and energy – the equivalence of seemingly different entities if we look deep enough).

- History (the non-linearity of cause-effect in society, the importance of small events, the Butterfly Effect in society, the importance of institutions, rules and beliefs, nothing is sacred or fixed -just human constructs that we decide to respect or idealize, the failed war against drugs). Why Nations Fail.

- Behavioural studies from psychology, management and economics. Predictably Irrational, Dialogue and the Art of thinking together.

- Macro-economics (e.g. interest rates and their effects on the economy, connectedness and interdependency in international trade, Ricardo’s ideas about specialisation and trade, effects on taxation in productivity). The Art of War and the Tao Te Ching.

- A few authors I admire: Bertalanffy, Einstein, F. Capra, David Bohm, Heisenberg, William Isaacs.

As a systems network builder, how do you fund yourself?

I do most of the network building out of pleasure. I love seeing connections happen. I fund this with my own resources and through specific consultancy projects.

My next questions

I am currently exploring how market systems development can contribute to the field of impact investment. Donor-funded programs introduce cultures, procedures and incentives into the organisations working to transform market systems that clash with a more organic, bottom-up, exploratory, endogenous approach. I think impact investment has the potential to do this if companies of different sizes and scopes have the right contextual (systemic) conditions to drive change that makes business sense while adding social and environmental value.

Common challenges in systems change

Power dynamics are always at play in systems change work. How do you build enough credibility to convene the best actors in a system? How do you get finance for your work when the people with the money often have a vested interest in things staying the same? How do you accept money from the power brokers of a system and keep questioning its foundations? If you are a funder, how do you get close enough to the actors in a system, to be able to make a fair assessment of the project?

These are some of the challenges I’ve spotted;

Power dynamics are always at play in systems change work. How do you build enough credibility to convene the best actors in a system? How do you get finance for your work when the people with the money often have a vested interest in things staying the same? How do you accept money from the power brokers of a system and keep questioning its foundations? If you are a funder, how do you get close enough to the actors in a system, to be able to make a fair assessment of the project?

Building trust To lead systems change you have to be someone who can hold their own with different players in the system. Heads of industry, regulators, entrepreneurs, activists. You need to be able to win genuine trust and build empathy for the different points of view. Sometimes this requires biting your tongue, rather than sharing exactly what you think because it's not helpful to the process.

Hosting You need to be a skilled convener because the process of hosting these communities is so key. Facilitation can be disastrous if done poorly, how do you get skilled up on this while juggling multiple other balls?

Measuring impact and securing funding systemic innovation takes time and requires emergent strategy. Funders are still learning how to back this kind of work and need to know outcomes and impact.

Overwhelm Hardly surprising given the above, acting on many places of the system at once and nurturing these varied communities can cause burn out. Your role involves bringing together a dissatisfied group of stakeholders, surfacing that discomfort, motivating others into action, nurturing these communities over the long term, whilst finding the words to report back on progress as it emerges to secure funding. This can be exhausting work and burn out is a common phenomenon.

Strategies for systems change: My presentation @Harvard, in summary

I have convened or been involved in multiple gatherings around systems change over the years (Leaders Shaping Market Systems, Systemschangers.com, Keywords, the SiX Funders node) and I am starting to see some patterns. Below I share some common strategies I see for intervening in systems, mapped onto Transition Theory.

Lorin Fries, Head of Food Systems Collaboration at the World Economic Forum and Ava Lala from Geneva Global and I spoke at the Harvard Social Enterprise conference in March on the topic of 'systems entrepreneurship'. Big thanks to Jeff Glenn for making it happen.

This is a summary of what I said.

Our audience at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government

Our strategy for systems change: The Finance Innovation Lab

The Finance Innovation Lab blustered into existence on a rainy Friday, as few weeks before Christmas. The financial crisis had just hit and the news was full of people leaving skyscrapers carrying their belongings and graphs with arrows pointing downwards.

I was working at ICAEW (The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales) and we came together with WWF to host a one off event. A 'Credit Crunch Brunch', as an experiment to see what would happen if we brought our two groups of stakeholders together. We convened them around the question 'how might we create a financial system that sustains people and planet?'

The event itself was pretty badly designed and badly facilitated. We didn't really know each other, let alone know what we were doing, but it didn't matter, it was totally oversubscribed.

We had brought together shiny suited accountants, lawyers and investment bankers, with environmental activists, corduroy wearing ecological economists who'd taken the train down from Cambridge University and twenty something economic justice campaigners. These were not people used to being in the same room together. They didn't read the same newspapers, their kids didn't go to the same schools, on paper they didn't really like each other very much. But if we did anything right that day, it was that we allowed them lots of time to talk to each other. And they started and didn't stop. By the end of the day we knew this was a project that needed to continue.

Over the next four years or so we worked first with Reos Partners and then with The Hara Collaborative to design a strategy for systems change. Our strategy was in simplified terms to:

- Convene a diverse group of stakeholders from across the financial system

- Host them at 150 person events

- Use participatory facilitation methods (namely Open Space) to get them organized into groups of people who wanted to change the same thing

- Experiment with different ways of supporting the most promising solutions that emerged from this process

Lots of these experiments failed of course, but some of them flew. The Natural Capital Coalition, grew from an innovation group in the Lab on 'internalizing externalities', its now a million dollar project supported by the World Bank and Rockefeller Foundation among others. Campaign Lab, designed to support economic justice campaigners, by teaching systemic strategy, is in its fourth year and AuditFutures, funded by the Big Four accounting organizations is innovating the future of the profession for society.

How did our experiments change the system?

When we emerged from the most busy period of the Lab and caught our breath, we tried to write it all up (see my blog on top tips I learnt from this painful process!). We came across Transition Theory and found it a very useful framework to explain retrospectively how our work was working towards systems change in finance.

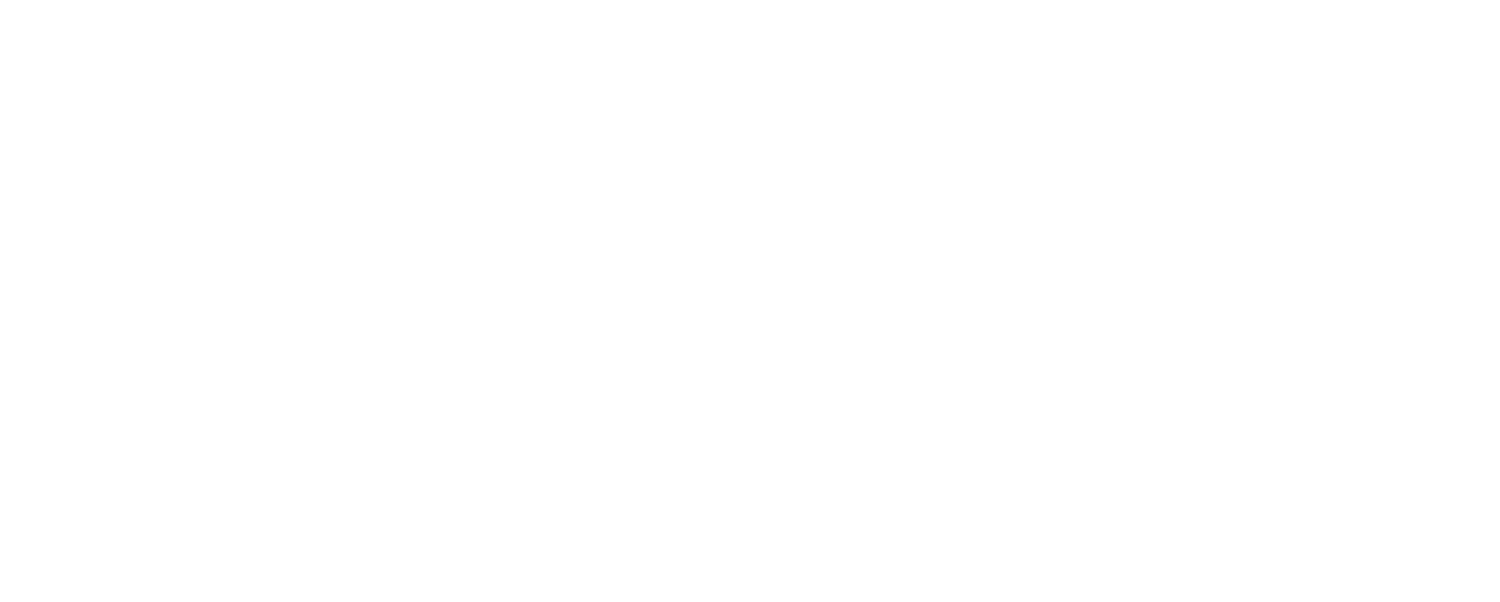

Transition Theory (Geels 2002)

The theory goes that if you want to try and change a system, you should work at multiple levels at the same time. He names three:

- Landscape This is the 'climate of ideas', culture, societies' world view. This is the slowest to change.

- Regime The Institutions, markets, organizations, companies we have built. The rules, policies and procedures that govern them. This is also slow to change.

- Niches of Innovation The pockets of innovation that bubble up and represent alternatives to the current regime. Often built on different values, or with a different culture to the mainstream system.

Some Finance Innovation Lab interventions

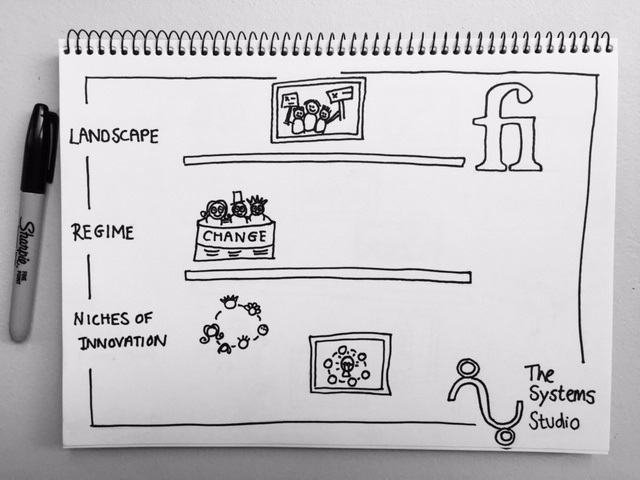

On reflection we saw that our experiments fitted into these levels:

- Landscape Campaign Lab was changing the 'climate of ideas' by supporting campaigners to be more effective at calling out the deficiencies of the system

- Regime Our Disruptive Finance program, brought together NGOs and think tanks across the system to lobby government to change the rules of the game in finance

- Niches of Innovation Simply by convening diverse people at 'Assemblies' and drinks we were helping to build a pipeline of new innovation. Helping to inspire and spark new ideas and to connect unconnected innovators. The Labs recently launched Fellowship program gets much more intentional about providing leadership support and community to pioneers who are innovating for good in the financial system.

Common strategies for systems change

For the last three years or so, I have been actively researching what everyone else is doing to change systems. Aware that we by no means had all the answers, I wondered 'what are other strategies for shifting systems?'.

This I think is a useful exploration because there is growing interest in how to 'do' systems change. A common challenge I hear from potential systems changers is 'The theory is too complex and I have no idea where to start.

I have convened or been involved in multiple gatherings around systems change over the years (Leaders Shaping Market Systems, Systemschangers.com, Keywords, the SiX Funders node) and I am starting to see some patterns. Below I share some common strategies I see for intervening in systems, mapped onto Transition Theory.

Common Strategies for systems change, mapped onto transition theory

- Landscape Tell stories yourself that point out the problems of the current system and highlight better ways of doing things. Engage the most skilled storytellers to do this for you; the media, campaigners and artists of all types. Create accelerators to support them to do this better.

- Regime Convene actors across the incumbent systems and get them organized to come up with a shared declaration of what they think needs to change. Help them lobby the institutions who set the rules. Support pockets of innovators within the system. Link them up regularly and build programs that make it ok to question the current regime. Take this one step further and build incubators where they can build ideas about how to do things differently, from within.

- Niches of innovation Convene diverse actors to spark inspiration and build a pipeline for new ideas. Create incubators and accelerators to turn the best ideas into reality. Fund these experiments. Fund an ecosystem of support of new ideas and actors. Build a 'demonstrator', a physical example like a sustainable ship or an innovative school, to 'prove it in a pocket', so it can spread.

Different types of system

Typically systems entrepreneurs spend a great deal of time connecting actors across their chosen system and use a number of the strategies above to intervene, at the same time. But the interventions they pick vary massively depending on the kind of system they are working on.

Different types of systems

You could be looking to shift an oligopoly in say food, finance or energy. You might be doing 'Pro-poor market development', mapping the supply chain of an inefficient market system in the developing world, like milk production, to see where you could fix broken links. You might be looking to shift an existing institution or organization itself, public service department or intergovernmental organization, or to build a new market system, like Gender lens investing, where one currently doesn't exist. You might be taking on a black market system, trying to uncover how it works and breaking it down. Or you might be convening actors from across all of these kinds of systems, trying to move many of them at the same time.

Characteristics of systems entrepreneurs

I ended my presentation by highlighting a few personality traits I'd noticed in the best system entrepreneurs I know. They are typically:

- Optimistic despite most people telling them repeatedly that change was impossible

- Open-minded a necessary trait for listening to the views of different people within the system, suspending judgment, being empathetic

- Patient systems change projects are slow by nature. Transformation and glory for a couple of years' work is unlikely

- Humble they are building a network of brilliant people who can work in new ways to change things. It's really not about one glorious leader, but rather someone who can cultivate the conditions for others to shine.

I can't help myself slip in a note and say that most of them are also women. I'm wondering whether this is because we are socialized to be diplomatic and patient, or that maybe that our presence in powerful systems is sadly still unusual, so creates a different vibe that allows people to behave differently. I'm not sure. A thread I'm definitely interested to explore in the future.

What do you think?

This is obviously an over simplification of strategies for systems change.

But honestly I think I'm on a mission to radically simplify systems change.

I know from my own experience how much potential it holds and at the same time it is so sadly missing from so many social change initiatives. I have seen that one of the most significant barriers to spreading systemic thinking is that currently the books, theories, maps and terminology are completely overwhelming. It's just too damn intimidating. I don't actually think it is that complex.

But I would love to hear your thoughts. Specifically:

- What other major strategies for systems change am I missing?

- What other kinds of human systems am I missing that are the subject of systems change initiatives?

My aim is to keep working on this and to create a kind of 'beginners guide to systems change' that is so simple that anyone can pick it up and get started.

Looking to create a strategy for systems change, but stuck? We can help you cut through the noise and develop a clear way forward. Get in touch rachel@thesystemstudio.com

The field of systems change is growing

"If no one shows up, I'm looking forward to listening to you guys anyway" we said to each other.

The 'we' was Lorin Fries, Head of Food Systems Collaboration at the World Economic Forum and Ava Lala from Geneva Global and I. We had been invited by Jeff Glenn to speak on a panel at the Harvard Social Enterprise conference on the topic of 'systems entrepreneurship'.

"If no one shows up, I'm looking forward to listening to you guys anyway" we said to each other.

The 'we' was Lorin Fries, Head of Food Systems Collaboration at the World Economic Forum and Ava Lala from Geneva Global and I. We had been invited by Jeff Glenn to speak on a panel at the Harvard Social Enterprise conference on the topic of 'systems entrepreneurship'.

The conference itself was on a Saturday. The Saturday before I moved our family from NYC to San Francisco, our apartment in boxes, the day before 20 4 year olds' were due to descend on my house for my daughters birthday party, and I had to catch a 3am flight to get there on time. Will this really be worth it? I thought to myself.

My doubt was compounded by what I had to say in my presentation. That social entrepreneurs are a different breed to social entrepreneurs. I described in some detail my experience as Co-Founder of The Finance Innovation Lab. How we had built an infrastructure of support for the social businesses in the financial system, but that when we looked up for support ourselves, we found it hard to find peers, let alone the awards, incubators and conferences the social enterprise movement enjoyed. Bitter? Well yes slightly.

But actually you know, it was worth it. My co-panelists were two sassy women who regaled fascinating stories of convening the CEOs of the worlds biggest food companies for tough talks at Davos and convincing major actors around sex trafficking in India to work together.

And seventy people turned up. Seventy. This was a major milestone for me. I have been tracking the emergence of the field of systems change practice in earnest for the last four years. You can read a publication I co-wrote with Tim Draimin on the topic last year, Mapping Momentum.

Sure, running the Lab was lonely, but if I was doing it again now, I'm not sure I'd feel so alone. SSIR has published 7 articles this year with 'systems change' in the title. HBR and Fast Company boast another a cluster each. Organizations from Acumen to Skoll to WEF are extolling the virtues of a systemic approach to social problems. Forum for the Futures School for Systems change has launched its Basecamp training program on systems change and funders are getting serious about how to support this kind of work. Things are moving in the right direction and I can't wait to see where we are this time next year.

Researching the field of systems change? We can help you cut through the noise and develop a clear way forward. Get in touch rachel@thesystemstudio.com