Mutiny at your workshop

Everyone who’s convened has been there.

Sometimes it looks like a huddle of people talking at lunchtime, avoiding your eye contact. It can be a friendly chat at dinner, “you should really do x”. Or a more direct hand up in plenary, "we've been talking and we just don't think we're focusing on the right thing."

Psychologists talk about ‘emotional contagion’. This is where one person's emotions and behaviors directly trigger similar emotions and behaviors in other people. Emotional contagion means that if you don't nip it in the bud, you can have a full blown mutiny on your hands.

In my experience, there are some important moves you can make to prevent it happening in the first place. Here they are:

Everyone who’s convened has been there.

Sometimes it looks like a huddle of people talking at lunchtime, avoiding your eye contact. It can be a friendly chat at dinner, “you should really do x”. Or a more direct hand up in plenary, "we've been talking and we just don't think we're focusing on the right thing."

Psychologists talk about ‘emotional contagion’. This is where one person's emotions and behaviors directly trigger similar emotions and behaviors in other people. Emotional contagion means that if you don't nip it in the bud, you can have a full blown mutiny on your hands.

In my experience, there are some important moves you can make to prevent it happening in the first place. Here they are:

What prevents you from hosting a successful gathering? What are the solutions?

All talk and no conversation

People get bored, frustrated, tired. Unable to remember of process all the information they have levelled at them.

Solution: Skip the presenters, allow people to talk. If it’s a technical topic people know don’t know enough about, have a punchy presenter and immediately allow time to discuss after each one.

The same people always dominate

The usual suspects, make their points first. Often these can also be the most passionate about the topic and or the most discontented, skewing the groups’ perception of the meeting.

Most of us have probably played both of these roles before. We know that both are frustrating. As the dominant person you are left feeling like you are not learning from your peers. As the quieter one, you leave having missed the chance to share your best ideas and often feeling like the dominant voice was not the most impressive.

Solution: Always use participatory processes. If nothing else, break people up into tables of 4, ask them a simple, powerful question about the topic in hand and make sure they record their answers on paper, so they know their ideas are being listened to.

If you want to do a better job, create the conditions for people to share their ideas through different mediums. Allow people to draw, build, talk, act and write. Not everyone explains best with words.

You don’t really care about this issue your asking people to talk about

People can see straight through it if you ask them a question about something you don’t really know or care about. Or if you ask for their ideas on an issue that you already have the answer to.

Solution: Many of us host rolling events that we ‘have’ to do regardless of whether we have something to solve. It’s always worth going back to ask ‘what was the purpose of bringing this group together in the first place?’ Was it to gather intelligence from an esteemed group of people? Was it to allow them to network and connect? These insights can often get up back on track, have them top of mind when you’re picking a design. Do you genuinely want to hear their ideas on an issue? What is the question you’d really love to ask them? If you are genuinely excited and interested in a topic, then don’t be afraid to express that. Be bold and tell a story about why this is important to you and ask your burning questions, not your average ones.

You are skating around the massive elephant in the room

If there’s dissent, it will only be amplified when you bring people together even if they don’t get a chance to speak to each other.

Solution: If someone takes a leap and brings up an issue that derails your plans, but you know if important, acknowledging it. If you have time split the group up and ask people to discuss and capture their key challenges on the topic. Even better, ask them to come up with solutions.

Your presence as a facilitator is shaky

Are you trying to do too much, overseeing the content, speakers, meeting logistics, design of the event and giving participants instructions too? Are you nervous, distracted or overwhelmed? This happens to us all, but you can make it less stressful by admitting to yourself that this is likely to happen if you don’t plan adequately.

If this is the first time you’ve convened a group, it’s natural to feel unsure how the dynamics will play out.

Are you asking yourself “who am I to convene this group?” This is such a common feeling for people who have taken action to convene for the first time.

Solution: Ask for help. Get better at delegation and if nothing else make sure you at least one person to help who can take control of logistics so you don’t have to think about whether you have lunch coming on time or enough post it notes.

Name your nerves when people arrive. Frame up the session by saying ‘We have never convened this group before. We don’t know what you’re thinking, what you care about, what opportunities or challenges you might face. This is an experiment for everyone. We will adapt the design to meet the needs of the group.’

If you look around and no one has taken the leadership to convene this group of people, then give yourself a big pat on the back for doing it and let that bolster your confidence.

Finally, simplify and breathe. Make your design and instructions as simple as they can be. Try and take 1 deep breaths before you start and stand feet forward and head floating up like a balloon (HT our brilliant former Ballerina Alina Faye who taught us this at our Remarkable Events workshop in July).

Your hosting team is shaky

This can happen for many reasons. If the core team don’t know each other very well, if there’s internal politics, if there’s a lack of preparation and roles have not been well divided up, it shows.

Solution: Spend at least 6 weeks planning a major event. Have weekly calls, expect your event design to pivot as new information comes to light, give yourself time to sleep on it and iterate it as you go.

You have the roles and responsibilities all mixed up

The right hand isn’t sure what the left hands doing. The hosting team is picked for their role in the organization, rather than for their skillset.

Solution: Make sure people are invited to contribute in ways they feel valued and comfortable. Someone might enjoy design more than facilitation. Others might be a confident at hosting the opening remarks. Another team member might be better at giving clear instructions or have the charisma to host the ‘fun’ sessions. Where possible play to people’s strengths no matter where they sit in the power structure of the team.

You are trying out a new event design that you’re unsure of

You feel nervous about whether it will work and you will never know until you are in the room on the big day.

Solution: Be proud of yourself that you’re learning. Spend a good 6 weeks, meeting for an hour each time, to go over and over this, refining it and making sure everyone is totally clear on how to run the session in advance. Have power point slides with clear instructions on the tables for participants and practice running through with colleagues until you feel good about it.

Yes, but

This is always one big fat experiment. Conditions are not always ideal. I have been designing and facilitating events for 10 years and I still make mistakes like these on a reasonably regular basis. The key is to have awareness about them in advance, to try to plan as much as possible and to make sure you spend time after each event thinking through:

What went well?

What would I do differently next time?

This is how we get better.

7 tips for designing great gatherings (and a few major don’ts)

Once you have a rough idea of why you are bringing people together and what you want to achieve, it’s time to set some clear, concise, powerful objectives.

You should end up with a maximum of 3 that should cover not only the kind of output you want from the meeting, but also how you want participants to feel when they leave.

Think about...

1. Is this a divergent or convergent conversation (or both?)

90% of your time pre-gathering should be spent on working out specifically what you are trying to achieve at the meeting.

Think about - is this a divergent conversation? i.e. You are trying to crack open a problem, gather a wide range of ideas, build on top of ideas and make the as big as possible?

Or Convergent one where you are sorting through ideas, making sense, evaluating what has emerged and clarifying the most prominent ideas in the room.

2. Objectives, Objectives, Objectives

Once you have a rough idea of why you are bringing people together and what you want to achieve, it’s time to set some clear, concise, powerful objectives.

You should end up with a maximum of 3 that should cover not only the kind of output you want from the meeting, but also how you want participants to feel when they leave. They should look something like this:

Gather a wide variety of ideas on x,y,z

Identify the most popular solutions

Build lasting connections between participants

Once they are set, workshop objectives become your North Star when you are trying to decide on a design. You need to refer back to them ALL OF THE TIME. Are we going to achieve these if we do x,y,z?

As you go through, you will need to set objectives for each element of your workshop design.

4. Put a time limit on the welcome and framing

Time to start putting together a draft design.

Step 1- who’s introducing the meeting? Think about your objectives here. Do you need to build credibility? Highlight a sponsor? Share some framing material you will be using in the meeting? Introduce the hosting team? You always need to give clear instructions about what participants can expect, but think about what’s the minimum they need to know before you get going?

Your aim here is to hit your objectives and try and keep intro’s to a maximum of 10 minutes. Any longer and it creates a boring start to the day.

5. Get people talking asap

Your room will spring to life as soon as you let people talk to one another. It will take the pressure off you to say something captivating and send a signal that this meeting will be ‘different’. Do this as soon as humanly possible.

When designing this big of the agenda, make sure you are thinking about how people feel as they sit in this room. How far they’ve travelled, if they know anyone else, if they might feel intimidated or excited to network, if they’ve had coffee yet. Set objectives based on this information.

You can do really simple things like ask participants to turn to the person next to them, and share why they showed up to the meeting, or more personal, like share what their name means. Get creative, but this is a vulnerable time in the design of the meeting, people often haven’t really ‘arrived’ yet, so make sure you do something that sets the tone for the rest of the session.

6. Design each session with your objectives top of mind

Take each of the overall meeting objectives you set out at the start of your design session and generate creative ideas about how to meet it.

If the first is something like ‘Gather a wide variety of ideas on x,y,z’ ask yourself things questions like - what’s the best way of getting everyone’s ideas (not just the dominant few)? How might we help participants generate as many ideas as possible in a short space of time? How are we going to gather these so that everyone can see them?

There’s a whole host of facilitation methods you can use (I will write about them in a separate blog), but this doesn’t have to be complex. Simply breaking up your group into small tables of 4 is often enough to turn a meeting from a dull roundtable to a fun, lively, productive workshop.

7. Work out how you’re going to capture insights

If you want to develop an idea of the ‘collective intelligence’ of the room, then it makes sense to gather and sort ideas then and there. My favorite way of doing this is to use ‘Bingo’. Ask each group to write down their top 3 insights, one each per post it, and share with the room, one by one. If any other group has the same or similar they shout ‘Bingo!’ and we stick these together on the wall. Two benefits to this method 1) it’s a quick way to show the most popular ideas in the room 2) it is fun, wakes everyone up and makes most people in the room smile.

If you want to do more in-depth analysis after the meeting, put some flip chart paper in the middle of the table and ask someone at each table to volunteer as scribe, to capture the main points of discussion. It’s lovely to design these sheets in advance, draw pictures on them, make them look nice. It helps to make sure people feel like their ideas are valued.

8. Close strong

End by thanking everyone and then move on quickly to what will happen next. What are you going to do with the precious ideas you’ve captured at your workshop? To do this you obviously need to have a plan in advance and to have thought this through. Planning a successful workshop always includes a plan for what you’re going to do in the short and medium term after it ends.

Major Don’ts

Don’t ask for your participants’ input, if you don’t actually want it

If you have already set the strategy, signed it off and are clear on you the way forward, don’t gather a group to ask for their ideas. It’s too late, people see right through this and it only causes resentment.

Instead find a problem you are genuinely stuck on. Something you are struggling to get your head around, where fresh ideas would help you find a direction forward. Invite a diverse group of people to help you solve it.

It’s ok to set boundaries, to say ‘I want your input on this part of the project, but not this bit’. If you’re leading the project, people will understand. Just never, never, never ask for participants input in a bid to try and ‘bring everyone along with you.’ What a waste of everyone’s time.

Don’t get excited and create an over complicated cringe-fest

Don’t start thinking of an exciting design for your workshop before you are crystal clear on your objectives. The most nauseating workshops in the world happen when you have ‘fun’ activities with no clear purpose. Put a lid on your creativity and unleash it only after you have used your rational brain to work out why you are hosting this event in the first place.

Don’t let presenters speak for too long

People can only concentrate for 20 mins at a time. You might be able to push this to 30 minutes if the subject matter is really interesting. Don’t send everyone to sleep by filling the agenda with back to back speakers. Guest start to get grumpy and they will always take it out on you. You can jazz it up easily with videos, or graphic recorders or table discussions half way through.

Don't forget this is a performance

People work better and feel more valued if they are invited to a beautiful space. Try and host your event in a room full of natural light. Remove unnecessary furniture, put flowers or candy in the middle of the table, space out tables, tidy up between sessions and have somewhere to put guests coats and bags. Decorate the walls of the room with the work you produce in the workshop as you go along. Make sure your instruction slides match and look stylish. If all else fails, plan a session outside or a brisk walk at lunchtime. Make sure you get a professional photographer to capture photos of the session so you can use them afterwards.

And don’t forget, you are on stage too

When you are facilitating an event, you are effectively holding the group of people together. I think of it a bit like choreography, or conducting, or even just being a good teacher. One of most significant roles during the day is your presence. If you leave the room, look at your phone, look bored when people feedback their ideas, gossip with your co-hosts in the corner, your guest will feel your lack of interest and become less motivate to participate yourself. I always know I’ve done a good job at facilitating when you go home utterly exhausted and brain dead. It’s part of the process!

Looking to host a great gathering, but not sure how? We can help you design and facilitate your event and teach you how to do it yourself. Get in touch rachel@thesystemstudio.com

The Challenge of Systems Leadership

At no time in history have we needed… system leaders more.”

— Peter Senge et al in their seminal 2015 SSIR article The Dawn of Systems Leadership

But, being a systems leader is hard work. It’s slow, painstaking, with many dead ends, limited fans and just when you think ‘why am I doing this again?’, a smattering of inspiring, life affirming moments that keep you committed to the cause.

This post first appeared on the Kumu Medium site

“At no time in history have we needed… system leaders more.”

— Peter Senge et al in their seminal 2015 SSIR article The Dawn of Systems Leadership

But, being a systems leader is hard work. It’s slow, painstaking, with many dead ends, limited fans and just when you think ‘why am I doing this again?’, a smattering of inspiring, life affirming moments that keep you committed to the cause.

If we need a pipeline of systems leaders to get working on our multiple interconnected challenges, we need to support them to do their work better and to stick at it when it gets tough. This starts with an understanding of the unique challenges they face. Here’s a few:

Being a systems leader makes you question your assumptions about everything

And that’s exhausting. Mapping systems and hearing multiple perspectives, you start to see how society, structured by our ancestors, continues to be reinforced by the institutions we are surrounded by. You hear the voices of the people who have lost out under those arrangements and see your place in the order of things, which is often uncomfortable.

I realized a year or so in that I’d been handed what I call ‘the colored glasses of culture’ at birth. A set of beliefs, behaviors and values for ‘the way we do things around here’. The more I delved into a systems approach, the more these assumptions were exposed and the more I questioned my own views. As a British person, for example, am I really supposed to be proud of Churchill and the British Empire? Is it ok that we partied so hard at University, while others can’t afford to attend school? At what age did I realize that being white was a ‘race’ too, not just a default? What does that mean for people of color?

The unraveling of things I was taught to take for granted has led to wave after wave of new awareness. It starts with a niggling cognitive dissonance that gets louder over time and prompts me to try and change my own behavior.

It’s much easier to get angry, much harder to listen, to understand and to try and change yourself. But systems leaders, if they are doing their work well, set out on a lifelong journey of self-discovery. As Senge et al say:

“Real change starts with recognizing that we are part of the systems we seek to change. The fear and distrust we seek to remedy also exist within us — as do the anger, sorrow, doubt, and frustration. Our actions will not become more effective until we shift the nature of the awareness and thinking behind the actions.”

Are you an expert or are you ignorant?

Vanessa Kirsch, Jim Bildner and Jeff Walker in HBR said of system entrepreneurs “They must have a deep understanding of the system or systems they are trying to change and all the factors that shape it.”

While Peter Senge et al said: “one of their greatest contributions can come from the strength of their ignorance, which gives them permission to ask obvious questions and to embody an openness and commitment to their own ongoing learning and growth that eventually infuse larger change efforts.”

While these insights might appear contradictory, I think they actually just highlight another dissonance systems leaders face.

As co-leaders of The Finance Innovation Lab, we had limited background in finance and as a result, our credibility to convene was called into question often. But as I noticed in 2011, my lack of knowledge was actually a strength. There were so many ‘positions’ we could’ve stood for within our community: ecological vs environmental economists, investment bankers vs alternative currency peeps, fintech vs impact investing. Everyone had deep knowledge of their territory. If we’d been advocates for one of these positions over the others it certainly would have cut the diversity of our project at the beginning.

You see, a systems leader is often a convener of difference. You have to know enough about the different positions within that system you’re working on to understand the dynamics at play, and then you need to be willing to suspend your assumptions when you host a gathering. If you show up with a strong agenda, siding with one group over another, your guests will spot it a mile off and it will significantly derail your work.

Unless of course you’re convening a ‘scene’ within the movement. And this is why your role is complex.

By a ‘scene’ I mean a set of actors who want to do the same thing — like a sharing economy group, a gender lens investing group, or a fintech for good group. In this case you are building a sense of camaraderie based on similarity. Here it helps to be a champion of the cause, to illuminate shared interest and support the group to imagine just how powerful they could be if they acted together.

A beginners mindset or a lack of understanding of the players, the issues, and the challenges is a stumbling block here. You have to know your stuff to have credibility and to have the power to convene a ‘scene’.

Perhaps being a systems leader is someone with a birds-eye view who doesknow what they don’t know. Not an expert, but a convener of them.

Are you an activist or a diplomat?

You have to care enough to act, but as a systems leader, while you have a personal view about what needs to change in the system, you must have the ability to authentically put those views aside when it comes to bringing people together. Geneva Global described that “Acting as a neutral facilitator…a networker, and a diplomat” are crucial capacities of a systems leader. Senge et al say:

“All change requires passionate advocates. But advocates often become stuck in their own views and become ineffective in engaging others with different views. This is why effective system leaders continually cultivate their ability to listen and their willingness to inquire into views with which they do not agree.”

This involves an ability to ‘suck it up’ rather than to ‘blow up’ when people attack you. That is why systems change process often leans on Buddhist and peace keeping techniques (and takes lots of practice). It comes from focusing on a vision for how things ‘could be’ rather than focusing on the symptoms that currently enrage warring sides. It can be really difficult and it takes restraint.

Collaboration is key, but bad collaboration hurts

Collaboration in systems change programs comes in two forms:

- As a systems leader you are almost certainly collaborating with people directly. This might be with key co-founders, funders, peers, networks, consultants. They will help you to convene diversity and support the ecosystem that emerges in ways you could never do on your own.

- You will be asking others to collaborate in new ways. As the host of a diverse ecosystem made up of relevant industry actors, innovators, policy makers, you will be asking them to do the same.

Learning how to collaborate yourself, teaches you a huge amount about how to create the conditions for others to do the same. It also keeps you humble because it reminds you just how hard it is to do well. This challenge is something Adam Kahane talks about in his book Collaborating with the Enemy, so I know I’m not alone on this:

“I have also wrestled with this challenge. At home, at work, in the community, I have at various times found myself needing to get things done with people I don’t agree with or like or trust. In these situations, I have felt not only frustrated, upset, and angry, but also baffled and embarrassed: how could I, a person whose work is to help people collaborate with their enemies, find it so difficult to do so myself? ….The most important lesson — obvious to some, surprising to others — is that collaborating with the enemy, although not fun or easy, is possible.”

You need to learn lots of new skills

Facilitation in the broadest sense is key to systems leadership. Your role involves facilitating an ecosystem of solutions to your systemic challenge: bridging, translating, connecting, building. But systems are different and what’s required in one project will not necessarily translate to another.

Daniela Papi-Thornton in her TEDx talk, highlights the range of skills systems entrepreneurs need to be successful:

“Real system change entrepreneurs are agnostic about the tools they use to create change. Yeah they might start a social business if that’s what’s needed, but if that doesn’t work… they’ll do something else. They will work with governments to get new policy, write a book, work with corporates’, work with non profits, be activists, they might even hug a tree from time to time.”

So being a systems leader means you need to have to be open to being a beginner again. To be continuously learning rather than enjoying your ‘expertness’.

In the Finance Innovation Lab we learnt coaching skills, design thinking, how to facilitate, business writing, network building, policy advocacy and tools for campaigning (among others). Some of this was funded by my organization at the time (ICAEW), but some of it we paid for ourselves and did in our free time.

Where next?

Systems leaders have a complex job to do and they therefore need thoughtful support. The School of Systems change are doing a great job at this. Tatiana Fraser and I are plotting a new program of support for systems leaders.

But we need more.

More incubators, more accelerators, more coaches, more mentors and more community.

Interview: Systems change network builders

Some things I’ve learnt:

- The people who live and breathe in the system are those who have to come up with the solutions to change it. Inputs from external experts are useful but they have to make sense to the people in the system.

- The system, not the poor, must be the unit of intervention if we want sustainable impact at scale.

- You have to listen to the system. Truly listen; without confirmation biases, without ego, without expectations, without intention, listen quietly and openly.

Benjamin Taylor

Benjamin has 20 years experience at public service transformation in the UK. As Chief Executive of the Public Service Transformation Academy, a not-for-profit social enterprise awarded the Cabinet Office Commissioning Academy, he is a leading thinker on system leadership, service design and transformation. He is an accredited power+systems trainer, a visiting lecturer in applied systems thinking at Cass Business School, City University, and has lectured at Nottingham Business School and Oxford Said/HEC Paris.

Some things I’ve learnt:

- Learn the difference between complexity and complicated, technical challenges.

- Dealing with complexity requires collaboration. To succeed co-design, enlist discretionary effort, be honest, accept you don’t have all the answers.

- Community is the antidote to uncertainty.

- To get more power, you have to give up control.

- Take time to ‘see’ the system. Think about illuminating the rules of the game, the effort and learning it takes to stay dysfunctional, the power of community.

- Listen out loud, ask good questions, start from strengths.

- Ask: Who do we want to be? What could I do to create a shared view across the whole system for the people in it? What thoughts or questions does this raise for me?

- Confront people with their gifts.

- Think massive, start very small. Help people to explore and experience change and shape it, within limits.

- Make your best prediction about how your changes will land. Take responsibility for all the outcomes, the actual experience of all the people in your organisation and all the people in your community, however great or sh*t it is. And as it turns out different from your prediction (because it will), think about why that is. Then you’ll be working in learning world too.

- Experimentation is the antidote to certainty, confront people with reality.

- Real change is dirty work. Don’t fool yourself you’ve learned anything until you have tested it in the real world. And even in the ‘real world’, don’t think you are learning if you’re not predicting and reflecting. When we take responsibility for learning about outcomes, we will get there

Some of the challenges:

I see the locus of challenges within our communities of systems practice, rather than externally:

- There are a growing number of systems ‘gurus’ who in my view are all about creating ownership to develop power. This is well covered by the title of a blog piece Richard Veryard wrote on a related subject: ‘Wrecking synergy to stake out territory’. (could you share the link, I cant seem to find this)

- There are ‘Systems Curmudgeons’, the people who stand on their expertise and attack those who ‘get it wrong’.

- And early-stage systems enthusiasts who create new movements that follow a ‘hype cycle’ which ends in failure, that is completely predictable to those who know the history.

- Funding can be a problem too – funding initiatives that take systems thinking out of managing business risk. Doing so makes programmes less organic, less well-adapted, and less effective.

- I think that the only way to counteract all of this is to patiently and consistently build network links, explain weaknesses and try to come up with an overarching narrative that talks about what each model explains, explains what they don’t explain, and explains why.

Systems of interest

I work on helping public services in the UK (and Australia) to transform themselves. More broadly, helping to change people's experiences of organisations, as employees and as customers/citizens. And, wider still, helping people to see systems and change them.

My systems change network

I am a systems change network enthusiast – more of a curator and a learner/sharer than a joiner. I work at the overlap of theory and practical organisational change. Some of the networks I’ve been involved in:

- SCiO – Systems and Cybernetics in Organisations – the best learning group I've experienced. It includes Practitioner development days and Peer speaker days with about 250 people. This is cheap and accessible.

- The London design and systems thinking meetup group (200+ folk)

- On LinkedIn, Systems Thinking Network and on Facebook, The Ecology of Systems Thinking.

- The ISSS and UKSS (International and UK Systems Societies). I am a visiting lecturer on the very interesting Cass Business School undergraduate Applied Systems Thinking course.

- The Public Service Transformation Academy, a not-for-profit social enterprise I founded, which supports capacity and capability building for public service leaders, and the Cabinet Office Commissioning Academy, which we run. The PSTA will publish its first annual 'State of Transformation' report on public service transformation in April next year - collaborators and sponsors are very welcome!

- Model Report is list I curate as a way of organising articles and links on systems thinking.

- RedQuadrant is a network consultancy which very much welcomes applied systems thinking. We work with about a hundred associate consultants a year from a pool of over a thousand.

My inspiration

- Barry Oshry's work –Power and Systems and The Systems Letter. Watch Barry at SCiO and PwC.

- Navigating Complexity, Arthur Battram

- Viable System Model, Stafford Beer – start with the explainers on SCiO then go on Beer, and try Patrick Hoverstadt's Fractal Organisations. Patrick’s Patterns of Strategy, co-authored with Lucy Loh, should transform the field of strategy and is enormously valuable in many contexts.

- For a 'the process as a system', try Joiner's Fourth Generation Management, Scholtes' Leader's Handbook and Team Handbook, for public services try Richard Selwyn's free Outcomes and Efficiency, dip a careful toe into I Want You to Cheat and other works by John Seddon and from the same stable, but stepping into ‘the community as a resource’ or strengths-based approaches, try Richard Davis' Responsibility and Public Services.

- For a beautiful little summary that goes way beyond its title, look for Total Quality Management by Develin.

- The Little Book of Beyond Budgeting by Steve Morlidge is another tiny read that sneaks systems thinking in by the back door and makes total sense, and Beat the Cuts by Rob Worth brings us back around to a Deming-esque view of public service processes (not necessarily systems – but critical to know).

- Try anything from Peter Block, especially Flawless Consulting and his work on Abundant Community. Anything from Marv Weisbord, particularly the short Tools to Match Our Values, and some Ed Schein... and I could go on! Adaptive Leadership by Heifetz and Lipsky is valuable too, as is the literature on 'wicked problems' and related concepts.

- I think there's little more powerful in organisational life than combining the Viable Systems Model with Elliot Jacques' Organisational thinking (updated, and with valuable additions, not all of which I agree with - in the brilliant but very academic Systems Leadership Theory by Macdonald et al). Luc Hoeboeke's Making Work Systems Better is perhaps the only work I know that combines them, as I do in my work.

- Two fairly recent additions are Ed Straw's video Stand & Deliver: How consultancy skills and systems thinking can make government work

- And I haven't even mentioned soft systems method, Nora Bateson's work… or the book I co-authored (not systems thinking in a meaningful way, but opening up thinking) - The 99 Essential Business Questions.

As a systems network builder, how do you fund yourself?

All pro bono! I can't help myself – I just find myself doing it – and I've never received a penny (well, about £150 per 'visiting lecture' – but that means forgoing a bit more income for a consulting day). We don't even pay expenses at SCiO. However, it shades right across my day job(s) at RedQuadrant and the PSTA, so I support myself somehow. One day I would like to make all my living in systems-related work, (though isn't every type of work systems-related?), and I certainly get amazing value from the networks I am in.

Interview: Systems change network builders

Some things I’ve learnt:

- The people who live and breathe in the system are those who have to come up with the solutions to change it. Inputs from external experts are useful but they have to make sense to the people in the system.

- The system, not the poor, must be the unit of intervention if we want sustainable impact at scale.

- You have to listen to the system. Truly listen; without confirmation biases, without ego, without expectations, without intention, listen quietly and openly.

Lucho Osorio-Cortes

A markets systems specialist at the BEAM Exchange and Practical Action Consulting. He has more than 15 years’ experience in international development and specialises in the facilitation of market systems development and organisational learning. Lucho coordinates The Market Facilitation Initiative (MaFI), a working group of the SEEP Network helping practitioners to become more effective facilitators of inclusive market development programs.

Some things I’ve learnt:

- The people who live and breathe in the system are those who have to come up with the solutions to change it. Inputs from external experts are useful but they have to make sense to the people in the system.

- The system, not the poor, must be the unit of intervention if we want sustainable impact at scale.

- You have to listen to the system. Truly listen; without confirmation biases, without ego, without expectations, without intention, listen quietly and openly.

- Market engagement is empowering in itself. We do not always need to empower ‘poor’ people before they are ‘ready’ to engage with other market actors.

- Never trust actors who always say yes and never question you as a facilitator.

- Never underestimate the transformational power of seemingly irrelevant actors. Let them ‘do their thing’ and pay attention to the reactions of the system.

- Every event in the system has the potential to change it, opening new, sometimes unexpected, entry points and closing entry points that we thought were open. Flow with the energy and rhythms of the system.

- Scaling up is a fractal process. The whole system has to resonate with the solutions implemented in a fragment of it. The more the fragment has the properties of the wider system, the easier the solutions from the fragment will be accepted and adopted by the broader system.

- Facilitation is not always equivalent to ‘light touch’. Facilitation is the creation of appropriate conditions for the market actors to change their system in ways that make sense to them, at their own rhythms and maximizing their own resources. Sometimes intense and long-term investments have to be made to get the system moving.

- Market systems can deliver sustainable impact at scale if three processes take place at the same time: empowerment for engagement, interaction for transformation and communication for uptake.

- We see what we measure; we measure what we value.

- Do your homework to avoid obvious mistakes but then jump in the water and learn as you swim.

Some of the challenges:

- Firstly, in my view there is a huge disconnect between theory and practice.

Theorists often say, ‘we get it’, but they don’t. What they don’t get is that the deeper you get into it, the more counter intuitive this work is. At the same time practitioners in the field will say ‘I have practical experience, I get systems’ and this is dangerous too. The two groups could learn a lot from each other.

- Secondly, people in development are often very keen on the ‘hard’ aspects of systems change; economics, viability, measurement and evaluation, program design.

Bureaucrats can digest this. But when you look at what makes or breaks a project, so often it’s the skill of facilitators. How they see the world and interact with it (e.g. the market actors and the forces that influence their behavior).

Facilitating systemic change requires skills and attitudes that bureaucrats can’t grasp and or measure easily with their current paradigms and practices. This makes it difficult for donors and other development agencies to invest because they can’t see the importance of the human element and the need to enable flexibility, uncertainty, trial-error-learning, and adaptability in the development process.

- Thirdly, the discourse of value for money dominates donors’ mindsets and is dangerously permeating the perceptions of the public.

But no functional system can be resilient without what I would call “exploratory inefficiency”. There is a risk that if we don’t produce evidence of the effectiveness of the market development approach the fad will go and donors will look elsewhere. But there is a paradox: under the traditional donor-implementer paradigm, the approach finds it very hard to deliver on its promise of sustainable impacts at scale and, therefore, to produce evidence of its success.

As a result of all this, MaFI is currently in the process of evolution from a general focus on market systems development to one on that explores the cognitive aspects of facilitation of market systems development programs. Questions like - how do successful facilitators behave? How do they think? What paradigms and tools they use? How do they identify key stakeholders and engage with them?

Systems of interest

I work on market systems and peer-learning networks in Latin America, South Asia and Eastern Africa. Most of my work is designed to help practitioners gain a better understanding of how to use a systems lens in their efforts to make markets more inclusive, productive and efficient.

If these practitioners are more effective at facilitating (enabling, catalysing) structural changes in market systems, more people will get out, and stay out of poverty for longer periods of time. This will happen with less effort, less cost and less friction, compared to traditional development approaches that focus on the poor and deliver solutions devised by experts from outside of the system.

My systems change network

The building blocks and principles that make up the field of market systems development have been around for many years, but the communities of practitioners who see themselves as part of this field started to form during the 2000s. There are many platforms where practitioners connect. I have been involved or participated in the creation of:

- The SEEP Network

- The BEAM Exchange

- The Latin American Network for Market Systems Development

- The Academy of Professional Dialogue

For example, I helped to create MaFI, which aims to close this gap in knowledge by advancing practical principles and tools that assist practitioners working in pro-poor market development to move from market assessments and program design to implementation.

During my time as the coordinator of MaFI (since 2008), the group has produced learning products based on MaFI's online discussions, webinars, and in-person meetings, and also seeks to influence the debate about rules and principles of international aid that hamper inclusive market development.

The value of the market systems development field is relatively big and growing. I would guess that, currently, there are around 20-30 market systems programs running, worth around $3-10 million each. Some people may argue that there are more market systems development programs but I have seen many of them that fail to use the principles of the approach properly. When it comes to the implementation of these programs, the devil is in the detail. For example, how you select and train your staff, how you build a culture that enables open sharing of mistakes and learning, how to change tactics and even strategy quickly, how to use less program money and more systemic resources, how to pay attention to early indicators of change that give you clues about the future behavior of the system; how to select, engage and communicate with market actors, how to help them experiment with new ideas, etc.

My inspiration

- Quantum physics (the duality of nature -e.g. light- and the need to embrace probability and uncertainty). The Tao of Physics.

- Theory of relativity (the importance of the different perspectives of the observers, the connection between matter and energy – the equivalence of seemingly different entities if we look deep enough).

- History (the non-linearity of cause-effect in society, the importance of small events, the Butterfly Effect in society, the importance of institutions, rules and beliefs, nothing is sacred or fixed -just human constructs that we decide to respect or idealize, the failed war against drugs). Why Nations Fail.

- Behavioural studies from psychology, management and economics. Predictably Irrational, Dialogue and the Art of thinking together.

- Macro-economics (e.g. interest rates and their effects on the economy, connectedness and interdependency in international trade, Ricardo’s ideas about specialisation and trade, effects on taxation in productivity). The Art of War and the Tao Te Ching.

- A few authors I admire: Bertalanffy, Einstein, F. Capra, David Bohm, Heisenberg, William Isaacs.

As a systems network builder, how do you fund yourself?

I do most of the network building out of pleasure. I love seeing connections happen. I fund this with my own resources and through specific consultancy projects.

My next questions

I am currently exploring how market systems development can contribute to the field of impact investment. Donor-funded programs introduce cultures, procedures and incentives into the organisations working to transform market systems that clash with a more organic, bottom-up, exploratory, endogenous approach. I think impact investment has the potential to do this if companies of different sizes and scopes have the right contextual (systemic) conditions to drive change that makes business sense while adding social and environmental value.

“The joy is in the journey”. Really?

When you think of evolving institutions, professions and organizations, joy isn’t necessarily the first word that springs to mind. Change is hard. It feels heavy, political, exhausting and serious.

But at The Systems Studio joy is front and center of what we do. It is our reason for being.

And here’s why- joy is a brilliant strategy for systems change.

What has joy got to do with systems change?

When you think of evolving institutions, professions and organizations, joy isn’t necessarily the first word that springs to mind.

Change is hard. It feels heavy, political, exhausting and serious.

But at The Systems Studio joy is front and center of what we do. It is our reason for being.

And here’s why- joy is a brilliant strategy for systems change.

What is joy anyway?

I was incredibly fortunate to be invited to a retreat a few years ago in Cape Town, with an organization called The Leading Causes of Life (LCL).

Led by a core team of academics and public health professionals they had been exploring the question ‘What creates a feeling of ‘life’ in the darkest of circumstances?’ We heard from incredible anti-apartheid campaigners share their stories of their lives torn apart, whilst still finding hope.

Over years of research, LCL have distilled their findings into 5 concepts that I use as design principles when bringing people together for systems change.

Design principles for joy

Create the conditions for:

- Agency – “I can do something to change this.” “My contribution counts.”

- Connection – Skip the small talk- design experiences where people can talk about things you really care about.

- Intergenerativity- Passing knowledge up and down the generations. Take this further and allow people of all levels of seniority to share experience.

- Hope – Create a sense that things can change for the better.

- Coherence - Help people make sense of how they think and feel about an issue and create the conditions for them to share this with the group.

To me joy is distinct from happiness or fun. you can't fake it. It requires facing the fact that things are imperfect. Getting the dirt out the cupboards and looking at it together. Being honest. Being vulnerable and admitting that we don’t have all the answers, even if we’re in charge.

Joy is a feeling that emerges during a workshop, retreat or gathering where people are able to connect in a meaningful way. It is life affirming, it is inspiring and it creates a bond between people that last long after your intervention. It also motivates participants to work on projects that are difficult and to keep going even when it gets really tough.

Bringing people together? Put the time into planning

So no it's not frivolous to spend ages working out who will sit where, or thinking through how to make introverts feel just as comfortable as extroverts.

If you want to bring people with you, to inspire and lead change, very often its those details that make your important gathering something they will remember forever, for all the right reasons.

Strategies for systems change: My presentation @Harvard, in summary

I have convened or been involved in multiple gatherings around systems change over the years (Leaders Shaping Market Systems, Systemschangers.com, Keywords, the SiX Funders node) and I am starting to see some patterns. Below I share some common strategies I see for intervening in systems, mapped onto Transition Theory.

Lorin Fries, Head of Food Systems Collaboration at the World Economic Forum and Ava Lala from Geneva Global and I spoke at the Harvard Social Enterprise conference in March on the topic of 'systems entrepreneurship'. Big thanks to Jeff Glenn for making it happen.

This is a summary of what I said.

Our audience at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government

Our strategy for systems change: The Finance Innovation Lab

The Finance Innovation Lab blustered into existence on a rainy Friday, as few weeks before Christmas. The financial crisis had just hit and the news was full of people leaving skyscrapers carrying their belongings and graphs with arrows pointing downwards.

I was working at ICAEW (The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales) and we came together with WWF to host a one off event. A 'Credit Crunch Brunch', as an experiment to see what would happen if we brought our two groups of stakeholders together. We convened them around the question 'how might we create a financial system that sustains people and planet?'

The event itself was pretty badly designed and badly facilitated. We didn't really know each other, let alone know what we were doing, but it didn't matter, it was totally oversubscribed.

We had brought together shiny suited accountants, lawyers and investment bankers, with environmental activists, corduroy wearing ecological economists who'd taken the train down from Cambridge University and twenty something economic justice campaigners. These were not people used to being in the same room together. They didn't read the same newspapers, their kids didn't go to the same schools, on paper they didn't really like each other very much. But if we did anything right that day, it was that we allowed them lots of time to talk to each other. And they started and didn't stop. By the end of the day we knew this was a project that needed to continue.

Over the next four years or so we worked first with Reos Partners and then with The Hara Collaborative to design a strategy for systems change. Our strategy was in simplified terms to:

- Convene a diverse group of stakeholders from across the financial system

- Host them at 150 person events

- Use participatory facilitation methods (namely Open Space) to get them organized into groups of people who wanted to change the same thing

- Experiment with different ways of supporting the most promising solutions that emerged from this process

Lots of these experiments failed of course, but some of them flew. The Natural Capital Coalition, grew from an innovation group in the Lab on 'internalizing externalities', its now a million dollar project supported by the World Bank and Rockefeller Foundation among others. Campaign Lab, designed to support economic justice campaigners, by teaching systemic strategy, is in its fourth year and AuditFutures, funded by the Big Four accounting organizations is innovating the future of the profession for society.

How did our experiments change the system?

When we emerged from the most busy period of the Lab and caught our breath, we tried to write it all up (see my blog on top tips I learnt from this painful process!). We came across Transition Theory and found it a very useful framework to explain retrospectively how our work was working towards systems change in finance.

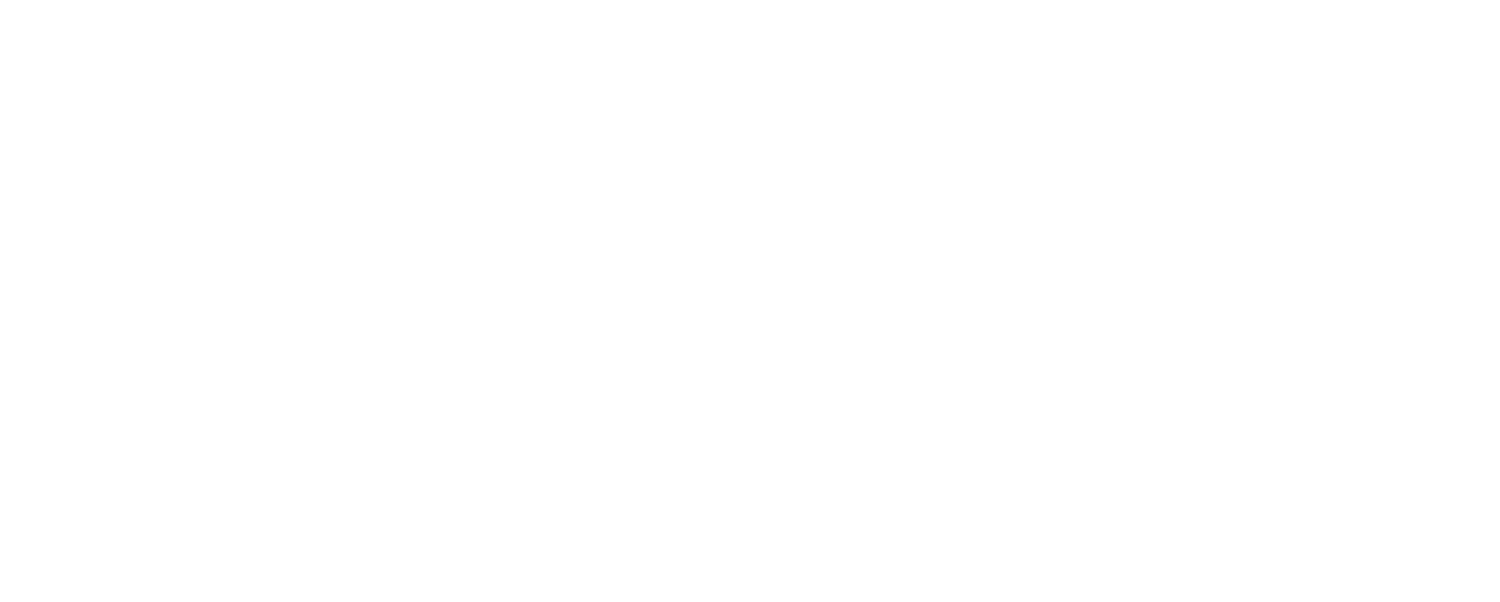

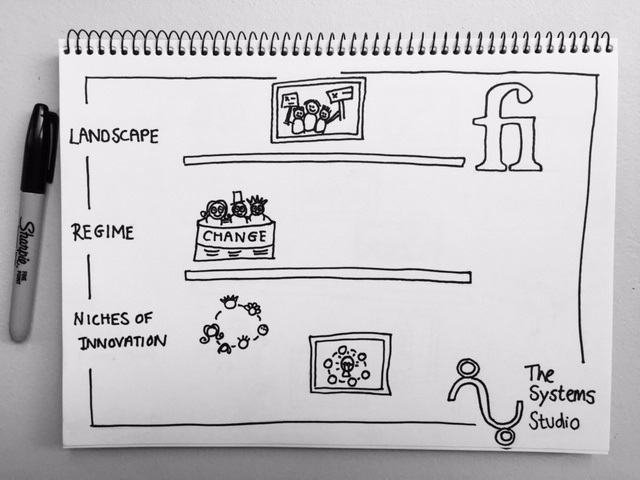

Transition Theory (Geels 2002)

The theory goes that if you want to try and change a system, you should work at multiple levels at the same time. He names three:

- Landscape This is the 'climate of ideas', culture, societies' world view. This is the slowest to change.

- Regime The Institutions, markets, organizations, companies we have built. The rules, policies and procedures that govern them. This is also slow to change.

- Niches of Innovation The pockets of innovation that bubble up and represent alternatives to the current regime. Often built on different values, or with a different culture to the mainstream system.

Some Finance Innovation Lab interventions

On reflection we saw that our experiments fitted into these levels:

- Landscape Campaign Lab was changing the 'climate of ideas' by supporting campaigners to be more effective at calling out the deficiencies of the system

- Regime Our Disruptive Finance program, brought together NGOs and think tanks across the system to lobby government to change the rules of the game in finance

- Niches of Innovation Simply by convening diverse people at 'Assemblies' and drinks we were helping to build a pipeline of new innovation. Helping to inspire and spark new ideas and to connect unconnected innovators. The Labs recently launched Fellowship program gets much more intentional about providing leadership support and community to pioneers who are innovating for good in the financial system.

Common strategies for systems change

For the last three years or so, I have been actively researching what everyone else is doing to change systems. Aware that we by no means had all the answers, I wondered 'what are other strategies for shifting systems?'.

This I think is a useful exploration because there is growing interest in how to 'do' systems change. A common challenge I hear from potential systems changers is 'The theory is too complex and I have no idea where to start.

I have convened or been involved in multiple gatherings around systems change over the years (Leaders Shaping Market Systems, Systemschangers.com, Keywords, the SiX Funders node) and I am starting to see some patterns. Below I share some common strategies I see for intervening in systems, mapped onto Transition Theory.

Common Strategies for systems change, mapped onto transition theory

- Landscape Tell stories yourself that point out the problems of the current system and highlight better ways of doing things. Engage the most skilled storytellers to do this for you; the media, campaigners and artists of all types. Create accelerators to support them to do this better.

- Regime Convene actors across the incumbent systems and get them organized to come up with a shared declaration of what they think needs to change. Help them lobby the institutions who set the rules. Support pockets of innovators within the system. Link them up regularly and build programs that make it ok to question the current regime. Take this one step further and build incubators where they can build ideas about how to do things differently, from within.

- Niches of innovation Convene diverse actors to spark inspiration and build a pipeline for new ideas. Create incubators and accelerators to turn the best ideas into reality. Fund these experiments. Fund an ecosystem of support of new ideas and actors. Build a 'demonstrator', a physical example like a sustainable ship or an innovative school, to 'prove it in a pocket', so it can spread.

Different types of system

Typically systems entrepreneurs spend a great deal of time connecting actors across their chosen system and use a number of the strategies above to intervene, at the same time. But the interventions they pick vary massively depending on the kind of system they are working on.

Different types of systems

You could be looking to shift an oligopoly in say food, finance or energy. You might be doing 'Pro-poor market development', mapping the supply chain of an inefficient market system in the developing world, like milk production, to see where you could fix broken links. You might be looking to shift an existing institution or organization itself, public service department or intergovernmental organization, or to build a new market system, like Gender lens investing, where one currently doesn't exist. You might be taking on a black market system, trying to uncover how it works and breaking it down. Or you might be convening actors from across all of these kinds of systems, trying to move many of them at the same time.

Characteristics of systems entrepreneurs

I ended my presentation by highlighting a few personality traits I'd noticed in the best system entrepreneurs I know. They are typically:

- Optimistic despite most people telling them repeatedly that change was impossible

- Open-minded a necessary trait for listening to the views of different people within the system, suspending judgment, being empathetic

- Patient systems change projects are slow by nature. Transformation and glory for a couple of years' work is unlikely

- Humble they are building a network of brilliant people who can work in new ways to change things. It's really not about one glorious leader, but rather someone who can cultivate the conditions for others to shine.

I can't help myself slip in a note and say that most of them are also women. I'm wondering whether this is because we are socialized to be diplomatic and patient, or that maybe that our presence in powerful systems is sadly still unusual, so creates a different vibe that allows people to behave differently. I'm not sure. A thread I'm definitely interested to explore in the future.

What do you think?

This is obviously an over simplification of strategies for systems change.

But honestly I think I'm on a mission to radically simplify systems change.

I know from my own experience how much potential it holds and at the same time it is so sadly missing from so many social change initiatives. I have seen that one of the most significant barriers to spreading systemic thinking is that currently the books, theories, maps and terminology are completely overwhelming. It's just too damn intimidating. I don't actually think it is that complex.

But I would love to hear your thoughts. Specifically:

- What other major strategies for systems change am I missing?

- What other kinds of human systems am I missing that are the subject of systems change initiatives?

My aim is to keep working on this and to create a kind of 'beginners guide to systems change' that is so simple that anyone can pick it up and get started.

Looking to create a strategy for systems change, but stuck? We can help you cut through the noise and develop a clear way forward. Get in touch rachel@thesystemstudio.com

Systems change: What makes it different from the rest of the buzz words?

Systems Change is about seeing a problem from multiple perspectives. Systems change initiatives typically work on many failures within the system at once. They are defined by their focus on the root cause of an issue, rather than solving the symptoms of a problem. They typically employ a combination of many interventions at once because one strategy will rarely solve a complex challenge.

Is systems change the new social innovation, collective impact, social labs? Is it an unnecessary buzz word that serves to exclude people doing good work? Why are we trying to define another term in the social impact space? And why does this concept have to be so impossibly difficult to get your head around?

Why do we need a systemic approach?

As Peter Senge says, problem solving can be like jumping on an air bubble in a carpet, you squash it in once place, only to find it pop up somewhere else.

What characterizes a systems change project?

Systems Change is about seeing a problem from multiple perspectives. Systems change initiatives typically work on many failures within the system at once. They are defined by their focus on the root cause of an issue, rather than solving the symptoms of a problem. They typically employ a combination of many interventions at once because one strategy will rarely solve a complex challenge.

For example as Co-Founder of The Finance Innovation Lab, my ambition was to support the emergence of a financial system that was in service of people and planet. To do this we supported new entrants to the financial system whose business' had a positive impact, we had programs designed to evolve mainstream finance and we supported civil society leaders to have greater influence on government policy. We did this all at once.

My brother who works in market system development in Myanmar for UN ILO maps supply chains, identifies weaknesses and creates interventions to bridge these gaps, working on multiple projects at the same time.

Defining systems change by the alternatives

How does a systemic approach interact with other kinds of interventions?

Social enterprise: typically a businesses designed to solve a single social or environmental problem. A social enterprise might for example, take food that otherwise would have gone to waste and turn it into products that can be sold. But this approach means that the enterprise is reliant on that waste for survival. If the waste ceases to exist, then so does the business. Taken alone, it doesn’t tackle the root cause of the problem.

These organisations as newcomers, often lack power and influence. They often rely on interventions elsewhere in the system for their success. So a group of social impact peer-to-peer lending entrepreneurs in the finance system for example, need regulation in order to launch and trade. An intermediary like Ashoka or Acumen might take a systemic approach, supporting only those social enterprises who are tackling root causes or by orchestrating collaboration across a complex problem and lobbying to remove market barriers to entry.

Social innovation: SiG in Canada argue that "For social innovations to be successful and have durability, the innovation should have a measurable impact on the broader social, political and economic context that created the problem in the first place". In the UK social innovation was often used to describe change initiatives in social service agencies in the wake of budget cuts. Others include social entrepreneurship within the definition of social innovation. At its heart, as Stanford University describe "A social innovation is a new solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, sustainable, or just than current solutions. The value created accrues primarily to society rather than to private individuals". This can be systemic or not, depending on the nature of the problem at its heart and on solution chosen.

Collective impact: A tool often used by systems leaders, this is about connecting and coordinating the efforts of a range of existing actors (policy people, social entrepreneurs, government agencies etc) to create more significant impact. The role of the core team at the heart of a Collective Impact project is one of the honest broker, an independent intermediary who bridges silos and brings people together in a way they wouldn't have done, without intervention. Collective Impact initiative helps them set a common purpose and to work towards mutually beneficial goals. See the work of Geneva Global who convened agencies, companies and NGOs around sex trafficking to great affect.

Design Thinking: A methodology for complex problem solving that famously follows a series of steps - building empathy with the user of the product or service, defining the problem you want to change, 'ideating' a solution (coming up with as many solutions as possible), prototyping the best of these ideas and testing them. Repeating the process until a successful intervention is created.

Super brain Alex Ryan who is steeped in both traditions described to me the difference between systems change and design thinking. He said something like, systems changers take a birds-eye view, while design thinkers take an ants eye view (I paraphrase!). Design Thinking works in harmony with a systemic approach when it comes after analysis of the dynamics of system you are trying to change. Otherwise you can come up with a brilliant solution to a symptom rather than a genuine root cause issue or a solution that users love, but the stakeholders that surround it, completely reject. See this great blog from Fast Company to read more.

Campaigning: Raising awareness of a problem that the system is creating or one it is ignoring. The ambition is to put pressure on the powerful organisations’ within that system to change behavior or the law.

This approach created a shift in corporate strategy for example, when companies like Nike were exposed for fostering child labor in their supply chain. Pressure from NGO’s and the media forced Nike to make sure children no longer worked for their suppliers. However the root causes of child labor remain, if this is all that changes. The problem is complex. Children were forced to go to work rather than school to help feed their families. But this choice meant their chances of escaping poverty in the future decreased as they were unable to read or write. Losing their job in the factory could have an even worse unintended consequence, like forcing children into prostitution to make ends meet.

This approach can help solve a single problem in a system, but the unintended consequences of that single change, often lead to further problems that require further campaigns.

Aid is another intervention. Fundraising in the developed nations to feed the poor in developing nations, for example. This approach works certainly in life and death situations, at times of drought or famine.

But the old adage ‘give the man a fish and he’ll feed himself for a day. Show him how to catch fish, and you feed him for a lifetime’, captures the limitations of this approach. Simply transferring funds keeps power dynamics intact with the poor dis-empowered to do anything to get themselves out of poverty in the long-term. You need to build infrastructure that lasts long after your intervention to make this work.

Thought Leadership initiatives aim to describe the problems of an existing system in reports and books and highlighting them at conferences and events where experts speak at panel sessions and round tables.

This approach is very successful at bringing issues to the attention of power brokers who steward a system and in spreading the idea of change within the different levels of a system. A place to make explicit criticisms which otherwise may go unsaid.

However thought leadership work if often criticized for its lack of action and events given the tag of ‘talking shops’. Ideas themselves do not always lead to change. Someone has to take the responsibility to actually do something differently.

For me systems change is not just about bringing together a range of actors for action, but about bringing together a range of tools to solve the problem in front of you. This typically means learning at some basic level about all of the above and beyond; policy change, to impact investing, to design thinking and everything in between. Or better still, it's about bridging the worlds between brilliant people who are masters at each of these interventions, and about asking for help, regularly.

Want to create a strategy for systems change and not sure where to start? We can help. Get in touch rachel@thesystemstudio.com